Pesticide risk study reveals data dilemma

It is a conflict. It revolves around one topic: data collection on golf courses worldwide. On the one hand, golf courses are coming under increasing public pressure, especially regarding water consumption and pesticide use. Given dwindling water resources and increasing health concerns as well as biodiversity problems with the use of pesticides on green spaces, the golf scene increasingly has to prove that its consumption is harmless. The only problem is that reliable data is (almost nowhere) available from golf associations worldwide. The data owners are the golf clubs or course owners – and they are often extremely reluctant to publish the data.

Study with US and European partners

This problem can be substantiated by a scientific study entitled Analyzing golf course pesticide risk across the US and Europe-The importance of regulatory environment 2023, which was published in the scientific journal Science of the Total Environment, but has hardly reached the golfing public to date. Nine American and European universities, scientific associations and golf associations were involved in the study. With the help of a survey of superintendents in the USA and Europe, the aim was to determine how high the so-called pesticide risk is in the respective countries. If you read the study more closely, you will see that although the final figures provide information on the pesticide risk in individual countries, the main question is how golf should obtain data in the future. Through regulatory obligation or through voluntary submission? The study clarifies that golf courses obviously cannot be relied upon to provide data voluntarily, even if the data is anonymized.

Response rate in the USA below 50%

“This study was primarily limited by the hesitancy of US-based superintendents to share pesticide records,” state the study’s authors, led by Michael A. Bekken. If all superintendents who participated in the resource efficiency survey had agreed to share anonymous pesticide data, the sample size in this study would have more than doubled. Of the golf courses contacted in the US, only 47 % shared their pesticide data, while in Europe 83 % were willing to communicate data. Where does this reluctance come from? The scientists do not provide a definitive answer but state: “It is unclear as to why US superintendents hesitate to share pesticide records which are reported in an anonymous manner but may be related to the concern that supplying records would damage the golf course’s reputation in its community, if published. Perhaps of greater concern to golf course superintendents may be that higher levels of public awareness of golf course pesticide use could lead to regulation that could limit the wide variety of pesticides currently available for use on golf courses in the US.”

Significantly higher pesticide risk in the USA

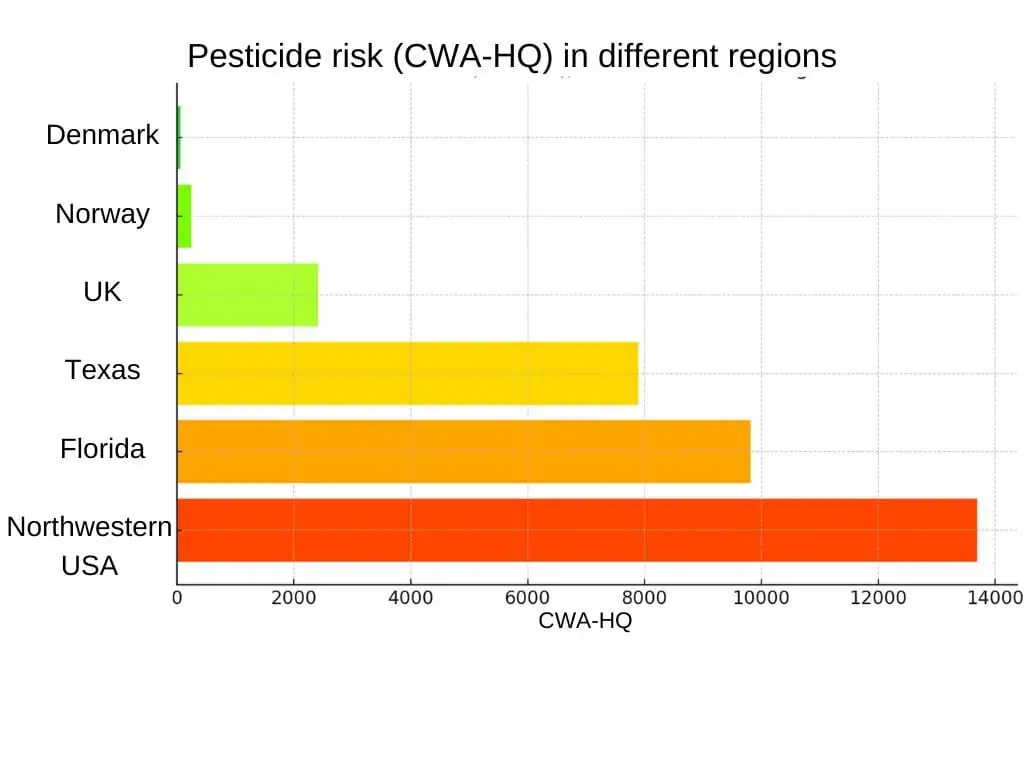

The study also makes this clear: based on the available data, the pesticide risk in the USA is many times higher than in Europe. However, there are also considerable differences in Europe between EU countries and the UK. In Europe, the pesticide risk was lowest, particularly in Norway and Denmark, where strict government regulations severely restrict the supply of pesticides. While greenkeepers in Denmark and Norway, for example, had fewer than 20 active ingredients at their disposal at the time the three-year study was conducted, there were over 200 in the USA.

What does the significantly higher pesticide risk mean for golfers? Anyone looking for relevant publications in scientific search engines will be disappointed. There are no recent studies. As a general rule, all products approved for use on golf courses are checked in advance by the national licensing authorities for health risks and, according to the authorities, are harmless. For example, the GCSAA, the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America, states: “Members are not only encouraged, but are required by law, to follow the product labels at all times. They also rely on the pertinent scientists’ recommendations, state and federal regulations and established Best Management Practices. This includes recommendations for selection, application, record keeping and more.” There is therefore no reason to assume that golfers’ health is at risk.

Pesticide use and biodiversity

The situation is different regarding biodiversity, which is known to play a major and very positive role for golf courses with their enormous areas. Numerous studies, particularly from the agricultural sector, point to the negative impact of pesticide use on pollinators, for example. But there is also a connection in golf. For example, the study Can a golf course support biodiversity and ecosystem services. from 2019 questions the extent to which the positive effects of a golf course on promoting biodiversity are counteracted by the negative effects of pesticide use on water quality or animal habitats. Given the extremely low use of pesticides in Europe, this question hardly arises, but because of the high levels in the USA, it certainly does.

So, what is the consequence of the realization that voluntary data submission is obviously a difficult issue? There was actually no reaction from the golf industry to the publication of the study, according to Michael Bakken. He was employed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison during the study, but now works for the Norwegian institute NIBIO. Both were involved in the research.

Obligation yes or no?

But how can the golf industry respond to the increasing demand for data from the public and the scientific community? Can golf associations oblige golf courses to publish water or pesticide consumption data? In principle, no. Only legislative authorities, such as the EU, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the USA or national and regional administrations are in a position to do so. This is another reason why the data situation in Danish golf, for example, is excellent by European standards. Here, the government’s permission to use pesticides in golf – albeit on an extremely small scale – is tied to the reporting of data.

This is why the United States Golf Association, which does a lot of training and information work in the field of greenkeeping with its Green Section and is also the most powerful golf association in the world alongside the R&A, points out that this power ends with the delivery of data: “The USGA is not a regulator, but a non-profit educator and investor that is one of many golf organizations that support best practices and widespread application of those practices. ,” says Janeen Driscoll, Director of Brand Communications. The same applies to the Golf Course Superintendent Association of America. When asked, however, the association did not explain why the willingness of their members to voluntarily disclose anonymous data during the study was so low.

A question of transparency

Does this leave regulation by the authorities as the last possibility to obtain data? Or is the negotiating position of the golf scene not much easier when balancing water, fertilizer or pesticide limits if an existing set of anonymous but meaningful data is already available? Ideally, this would prove that the consumption of water and the use of chemical fertilizers or pesticides on golf courses may be far lower than the public assumes. In general, data publication always paints a relatively positive picture of transparency. In most cases, Europe’s and America’s golf courses still need to be convinced of this transparent approach.

Currently, the golf club or golf course operator is the master of its data. They can decide whether to publish it or not. They cannot influence the public reaction to it: anyone who does not publish data and is not transparent quickly exposes themselves to the assumption that they are hiding something negative.

Conflict issues for the golf associations

The golf associations are therefore in a quandary: do they make themselves unpopular with golf courses and golf clubs because they are increasingly demanding voluntary data entry from them? Or do they continue to convey the image of a non-transparent industry to national or international authorities? The data dilemma is forcing the golf associations into a dilemma. Can they win this game?