Sustainable greenkeeping: The Danish approach

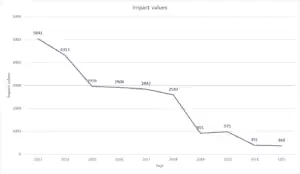

Greenkeeping is not primarily about growing grass. That’s the phrase we kept coming across on our research trip to Denmark. When discussing the question of what sustainable greenkeeping will look like in the future, the name of the Scandinavian country comes up again and again. Denmark is regarded as a pioneer of sustainable greenkeeping, which for years has relied on significantly less use of pesticides and nutrients than is usual in other parts of the world. This is largely due to the fact that the Danish Golf Association already completed a reporting on nitrogen and phosphorus consumption as part of a green audit in 2003 and has been collecting precise data on the use of pesticides on golf courses since 2013.

Effects on quality

Directly linked to this is the question of how the quality of golf courses is affected by such an approach. Anyone who gets to the bottom of this question quickly realizes that it is about far more than just sheer numbers. Rather, when talking to the Danes themselves, it becomes clear that the fundamental question of what sustainable greenkeeping means is at the center of the discussion.

We discuss this question with three head greenkeepers in the Copenhagen area: Per Rasmussen, Course Manager at Smorum Golf Club, a course that has been attracting attention for a number of years with enormous sporting successes. Martin Nilsson, head greenkeeper at the Royal Copenhagen Golf Club, the oldest golf club in Scandinavia, which is located on the grounds of an Unesco World Heritage Site. The use of pesticides of any kind is strictly prohibited here. And then there is Gediminas Rudokas from Brondby Golf Club, who took on the role of head greenkeeper in 2018 and has since been working to transform green areas that were completely matted, overwatered and in poor condition due to inadequate maintenance.

So when researching for this article, we look at greens together. Again and again. We touch the grass surface and talk about the green hardness. About how diseases spread when there are no more pesticides, and how long it takes for green spaces that used to crave water and fertilizer to switch to fewer nutrients. However, they receive more attention than before.

Communication to the golfer is crucial

This is actually a discussion for agronomists or greenkeepers, because it’s easy to slip into talking about grass types, nitrogen levels or water constituents. The thing is, the normal golfer doesn’t understand any of this anyway. He wants to play golf. Preferably on good greens. In the end, however, the normal golfer must understand why greens change in colour, consistency and playability if the pesticide ban, which has been discussed for some time but has not yet been decided, is actually introduced within the European Union.

Patience during the changeover

In the course of the discussions with the three Danish greenkeepers, several cornerstones of the work crystallized. Knowledge, patience and support – these are the three terms that keep coming up in conversation.

Each of the three men originally learned greenkeeping the way it has been done for decades, with lots of input of nutrients and water. “Then, in 1998, I came into contact with a British group that was primarily dedicated to greenkeeping with fescue grasses,” recalls Rasmussen. A new world with new knowledge opened up. It was less about the beautiful deep green grass on the surface and more about the roots growing deep down and getting their nutrients and moisture from there. The green surfaces should be robust and healthy and develop resilience against diseases. “We are greenkeepers who work in cool climates,” adds Nilsson, which is an essential comment. The so-called fescue grasses do not feel at home in every climate.

Nevertheless, the three men’s approach is relevant for the whole of Europe because it also has a great deal to do with the other two terms. Patience and support.

The conversion of greenkeeping is not a procedure that works overnight. Rudokas is standing in front of a green at Brondby Golf Club, which is in the middle of this transformation phase. In a positive mood, he looks at a surface that shows different types of grass in different colours, but is not matted and also looks good to play on. “First I had to get rid of the thatch,” he recalls. In the first year, it aerified the surface of the green three times with large spoons. This procedure is often a horror for golfers because it takes several days for the grass on the greens to form a uniform surface again.

The thatch in the surface at Brondby Golf Club became less and less, and the procedure was required less and less every year. “I didn’t need them for the first time in 2023,” explains Rudokas. The term “ninja needles” is used when the three greenkeepers explain what the ultimate goal is: to work the greens with very fine spikes that cause only small cracks during aerification and do not interfere with play. Depending on the initial stage of the greens, however, it can take a few years to achieve this goal. As I said, you need patience.

Above all, however, the greenkeeper needs the support of the board and management: “As a greenkeeper, you absolutely have to believe in what you are doing and stand your ground,” explains Nilsson, now also Vice President of the European greenkeeper association FEGGA. Only those who can credibly explain a strategy to the members and the executive committee and back it up with data can ultimately hope to be successful in changing the greenkeeping strategy.

After all, no one is immune to setbacks during the transformation process. “Of course there’s pressure, which you also put on yourself,” Rasmussen recalls of his initial phase at Smorum Golf Club. “But I managed to convince the club managers that this is the best way to manage.” Unlike his colleagues, he applied another fungicide just before Christmas last year in order to get through the winter well. In a club with over 3,000 members and high sporting standards, he realized that it would be difficult to completely do without pesticides.

“We definitely want to reduce the use further and are in agreement with the government on this. But we also need products for emergencies,” explains Torben Kastrup Petersen from the Danish Golf Union who is responsible for sustainability, among other things. However, the reporting of all clubs in recent years has documented that the use is minimal. Confidence in the approach of the golf courses has grown on the government side as a result. Transparency, he recommends to other golfing nations, is the first path to success.

The greenkeepers on site see it the same way. Communicating their methods and goals gave them the backing they needed to establish a new management model. Now they are sitting together and talk about their vision of sustainable greenkeeping. The visitor does not understand every technical term. But one thing is clear: in this case, greenkeeping means passion – the passion to work more sustainable in the long term.