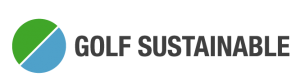

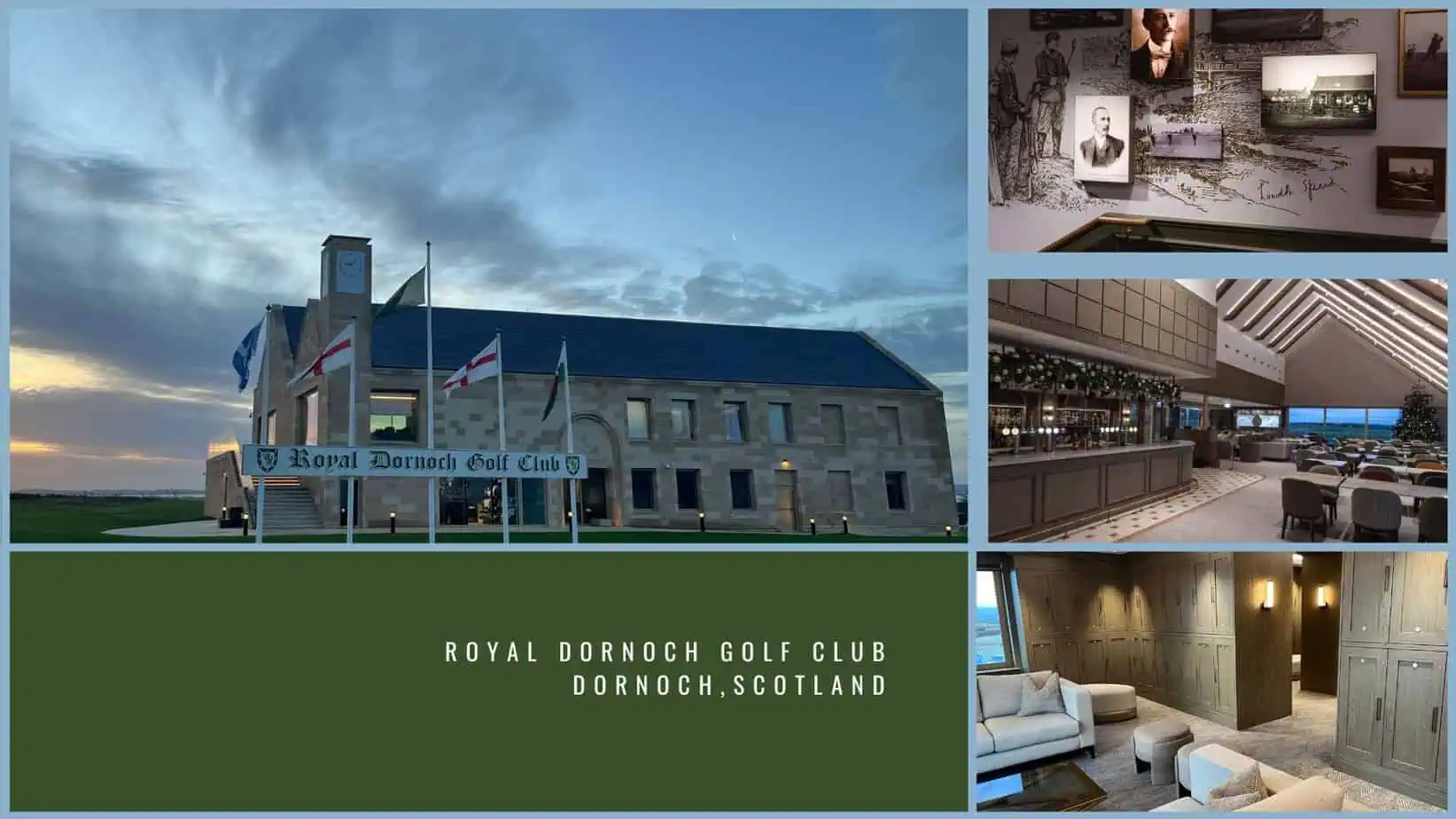

Now it stands there: stone and grey, just like all the buildings in the small town of Dornoch up here in the Highlands. The new clubhouse of the world-famous Royal Dornoch Golf Club, which opened in mid-December, is designed to last at least another century. After all, its predecessor lasted 116 years. It looks majestic as it sits above the two golf courses. No wonder that enthusiastic comments have been flooding in on various social media channels over the past few weeks. But the reaction of the members has also been “amazing”, says General Manager Neil Hampton. “The exterior had mixed opinions until the scaffolding and hoarding came down. When people could see the building for real, it did change many minds. The inside has been a hit with everyone. The interior design team really grasped the brief and has given us “our” club.

What is hardly mentioned in all the enthusiastic comments is the fact that this clubhouse is now probably one of the most sustainable clubhouses the UK has to offer.” With the opening of the £13,9 million building, a balancing act has been achieved between historical aesthetics and radical technical innovation, a task that, according to architect Fraser Davie from Keppie Design, was by no means easy.

A design that is ‘hidden in plain sight’

The architectural theme of the project was the seamless integration of state-of-the-art environmental technology into a classic exterior. Davie calls it hidden in plain sight, meaning that the technology is there, but you can’t see it. “Actually, we take it as a compliment when observers remark that there are no solar panels”, he says with a smile when talking about the south-facing roof: the entire roof area consists of a 45.56 kWp photovoltaic system, which is colour-matched so precisely to the natural slate that it is hardly recognisable as a solar system to the untrained eye. This ‘build less’ approach made it possible to use the PV panels directly as roofing, thus saving valuable material.

Covid pandemic as a catalyst

According to Neil Hampton, sustainable architecture was by no means as relevant in the initial considerations in 2018 as it later became. It was only with the Covid pandemic and the rise in material and energy costs that the assessment changed: “When we restarted the project after a 2.5 year hiatus there was a much bigger consideration on how we spend our money on the building, and then the running of the building.”

While the decision for the geothermal heat pump was made from the beginning, the decision to install a comprehensive solar system was taken post Covid, partly to counteract the exploding energy costs.

A steel skeleton with slate and sandstone

Despite its traditional sandstone and slate façade, set within a steel skeleton, the building achieves Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating A. The technical specifications are impressive for a building in such an exposed coastal location:

• Heat source: A ground source heat pump (GSHP) with 12 boreholes at a depth of 120 metres provides heating and cooling. It was preferred over air-source heat pumps because it is visually unobtrusive and does not produce fan noise.

• Insulation: The U-values of the building envelope (walls: 0.20; roof: 0.15) not only exceed the 2019 standards, but are already above the planned UK standards for 2025.

• Climate resilience: Due to the strong winds on the Scottish coast, a stone and slate palette was chosen, which, according to Davie, should give the building a lifespan of 100 years.

• Use of glass surfaces: To maximise the view to the south, east and west, glass with optimised G values (solar factor) was used to limit solar radiation. In winter, passive solar gain provides additional warmth, which can be regulated by internal blinds and thick curtains.

• North façade: Smaller openings to minimise heat loss.

• The entire kitchen is electric.

No compromises

Davie also makes it clear that compromises were necessary, if only because otherwise construction costs would have continued to skyrocket. While the interior walls were filled with timber for ecological reasons, steel had to be used for the basic framework to ensure the flexibility of the large catering areas. Here, large sliding doors allow the size of the rooms to be changed in size.

There were also limitations in sourcing materials: as there was no local sandstone supplier, stone from Yorkshire was used. The slate for the roof comes from Spain, as Scottish slate would have been three times as expensive. Yes, says Davie, these transport routes are not ideal, but the balance between budget and sustainability is also important.

A clubhouse for the community

For Neil Hampton, it is crucial that the architecture of the clubhouse continues to reflect the open character of the club, regardless of its ranking among the best and most famous golf courses in the world. The clubhouse is designed to be flexible for community events. Involving the entire population of Dornoch through golf is extremely important to Hampton. Social sustainability is one of the key elements of the club. This also benefits the top players: the changing rooms are modular in design so that they can be adapted for large-scale men’s or women’s tournaments, such as the 2028 Curtis Cup.

The battery issue: safety first

A special chapter in the clubhouse’s construction history is the accommodation of the solar batteries: ‘The proposal to house the batteries for the solar panels inside the building caused us enormous headaches,’ he recalls. The original plan was to place the 33 kWh battery storage system inside the building. The architects had already created a particularly safe, non-combustible environment for this purpose, consisting of concrete walls and a solid concrete slab to eliminate any risk. ‘No chance’ was the insurer’s verdict on placing it inside the building. As a result, the batteries had to be moved to another area. This eliminated any fire risk to the historic clubhouse structure, while still allowing the energy generated to be stored efficiently, for example, to take advantage of cheap nighttime tariffs.

Sceptics on the subject of sustainability often argue that installing solar panels so far north does not make sense, as there is insufficient sunlight. Davie quickly dismisses such criticism: Even without direct sunlight, a battery solution is sustainable and efficient, as it allows cheap night-time electricity to be purchased when there is a surplus in the grid. This saves the club money and reduces the load on the grid. At Royal Dornoch, the estimated cost of sustainable technologies is expected to have paid for itself in 10 years.

All images: Royal Dornoch Golf Club

All images: Royal Dornoch Golf Club