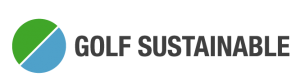

“We want to see a sea of heather.” As Michael Mann, Superintendent of the English Walton Heath GC, says this, he stands on the Old Course of the world-famous golf course and points with his hand to the golf holes that stretch across the open terrain. There is heather in every form on the 36-hole course in the Surrey region outside London. Freshly sown or as small shoots, as dense clumps of gnarled flat woodland bordering the fairways or as waist-high bushes further away.

The golf course has become famous as a Ryder Cup venue or as the venue for numerous world-class events. The 1981 Ryder Cup was held here, and the qualifying tournaments for the men’s U.S. Open and the AIG Womens Open take place here every year. However, it owes its unique character to the nine hectares of heathland that the club has dedicated itself to maintaining and expanding for more than 25 years.

A tour of the two championship courses with Michael Mann is therefore also a great lesson in heather restoration. Over the course of a few hours, we will crawl on our knees between the plants looking for pests, distinguish between healthy and damaged heathland and examine areas of bare ground that at first glance look like unkempt areas. In a few years, however, the brownish soil will have grown back into healthy heather.

Before his start at Walton Heath, Superintendent Michael Mann had already dealt with ambitious golf on the one hand and sensitive natural areas on the other at the golf courses of Wentworth and West Hills. However, the extreme focus on heathland is exceptional at Walton Heath. Here they cultivate their own heather sods and produce the seed themselves. In firmly established maintenance sections, heathland areas are either completely replanted, cleared of brushwood or bushes. Only this continuous care leads to flowering plants that are resilient to pests, diseases and golfers and their shots.

A defined heathland management plan ensures controlled processes. In coordination with numerous partners such as GEO and Natural England, it has been possible to create a harmonious coexistence between heathland and golfers. The golfer’s game is just as unpalatable to the plants as the plants are to the golfer’s game. Sand that is played from the bunkers into the heather fronts of the obstacles is just as damaging to their development as players who persistently work their way through the plants with their clubs.

However, they are treacherous and the biggest obstacle on two golf courses that are maintained in the style of links courses – with hard surfaces, fast greens and bunkers as real obstacles.

https://golfsustainable.com/en/the-golf-course-as-part-of-a-sponge-city/

“We think it’s great that we can use nature to our advantage,” says Mann, explaining the approach. The heather plants create visual stimuli, but are also a strategic element because balls can disappear, never to be seen again, even on overgrown bunker embankments.

Nine hectares of healthy heathland now represent an important value for the Surrey region. According to estimates by the environmental authorities, around 85 percent of heathland in the sandy region has been lost over the past 200 years due to scrub encroachment, the construction of settlements and industrial areas. According to the State of Surrey’s Nature report, a total of around 4,119 hectares remain. This means that Surrey is home to around 13 percent of the Lowland Heath remaining in the whole of Great Britain.

Golf courses such as Walthon Heath Golf Club create small but valuable heathland areas with their commitment, which is also reflected financially in numerous hours of heather work by the greenkeepers. The age mixture of the plants reduces the fragility of the stands.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

News & trends around the topic of sustainability in golf

Michael Mann has become a real fan of heather plants through his work at Walton Heath. “I don’t think I’ll ever get bored of them,” he explains, looking at an area whose slightly different color immediately indicates a disease to the expert. “We have to take it out,” is the analysis. He will dig up the affected area and reseed it. And then he will wait. It can take four to five years for the plants to achieve proper growth. “You definitely need patience,” he says. “But it’s incredibly satisfying work.”

Image: St. Andrews Links Trust

Image: St. Andrews Links Trust